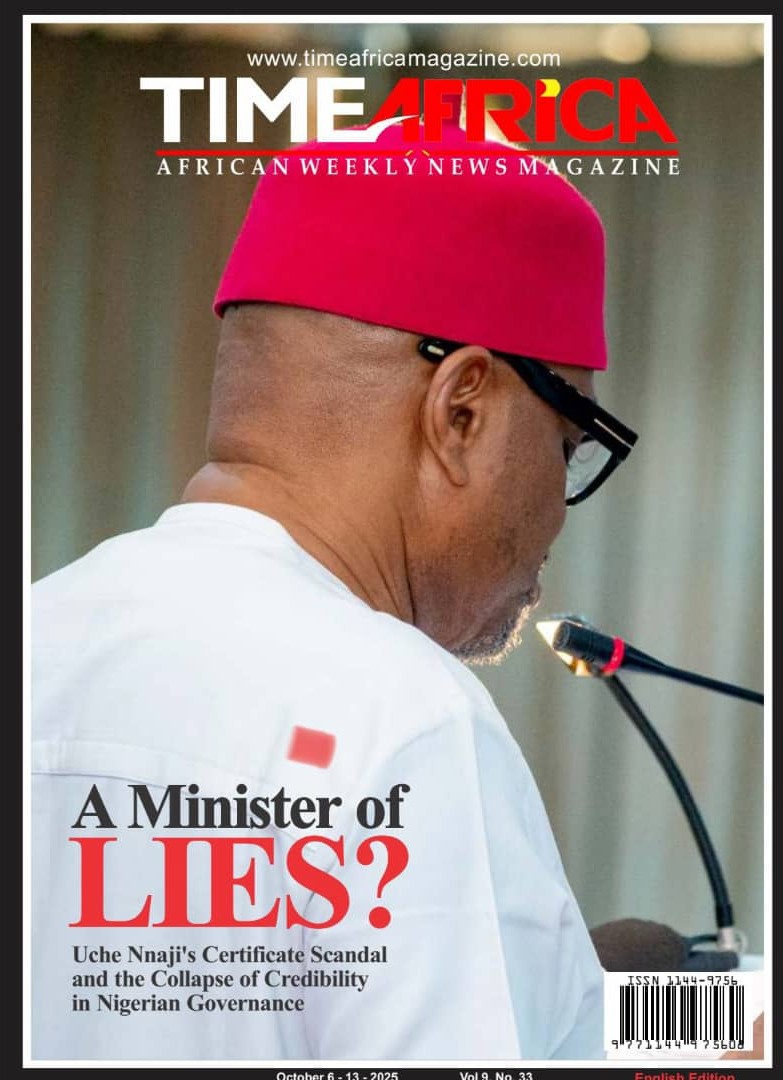

In July 2023, as President Bola Ahmed Tinubu unveiled his first ministerial list, one name stood out—Geoffrey Uchechukwu Nnaji, a man touted as a “visionary industrialist,” nominated to head the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology. His 10-page ministerial profile overflowed with accolades: scientist, oil and gas expert, construction magnate, healthcare visionary, pro-democracy activist. But beneath the polished veneer was a fundamental lie—one that, two years later, has unravelled spectacularly before a shocked nation.

Uche Nnaji has now confessed, in sworn court documents, that the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN) never issued him a degree certificate. That admission validates what had once seemed an outlandish claim: that the credentials he submitted to President Tinubu, the Nigerian Senate, and national security agencies were forged. The degree and National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) certificate he used to ascend to one of Nigeria’s most prestigious cabinet positions are, according to extensive investigative findings and now his own admission, counterfeit.

The public revelation, buried in a 34-paragraph affidavit Nnaji submitted in an ongoing lawsuit, amounts to a political and legal earthquake. His attempt to use the courts to block UNN from “tampering” with his academic records backfired catastrophically, when, in paragraphs 12 and 13, he conceded that while he completed the programme, the university never gave him a degree. That would mean, logically and legally, that he could never have qualified for the NYSC programme—a separate credential he also submitted, and which independent analysis has now concluded is also fake.

For months, journalists from PREMIUM TIMES pursued the truth, conducting an exhaustive two-year investigation that pieced together inconsistencies, matched graduation rolls, analysed registry responses, and interviewed senior university staff. The conclusion: Nnaji never graduated, never earned the degree he claimed, and therefore never legally qualified for national service.

Despite these serious revelations, Nnaji had, until now, refused to speak to the press. Repeated attempts to reach him for comment—emails, letters, phone calls—all ignored. Then, almost inadvertently, he spoke where it mattered most: in court. In an attempt to shield himself from further scrutiny and force the release of his academic transcript, he provided written testimony that effectively confessed to what had been alleged all along.

Yet the scandal is not merely about personal dishonesty. It is about the architecture of Nigerian public vetting, the ease with which forged documents pass through layers of security and legislative checks, and the alarming vulnerability of national institutions to deception. It is a story of systemic failure, of wilful complicity, of elite impunity.

Consider the facts: In his profile submitted to the Senate Clerk ahead of his August 2023 confirmation hearing, Nnaji claimed he earned a combined degree in Biochemistry and Microbiology from UNN. He did not specify the year of graduation. He also claimed to have served as a laboratory supervisor at the University of Jos Teaching Hospital under NYSC in 1985, and later at Jos International Breweries in 1986. Attached to this profile were copies of the alleged degree and NYSC certificates.

PREMIUM TIMES scrutinised these documents. The degree certificate bore irregular fonts and a suspicious signature format. The NYSC certificate raised multiple red flags. It was signed by an NYSC director who was not in office at the time. It listed a service duration of 13 months, instead of the standard 12. Most damningly, the supposed NYSC title of “National Director” did not even exist in the 1980s.

Back at UNN, an initial letter from Registrar Celine Nnebedum in December 2023 seemed to give Nnaji a lifeline. The letter, sent to the People’s Gazette, stated that Nnaji had indeed been admitted in 1981 and “graduated” in July 1985 with a Second Class (Lower Division) degree. But within months, the university retracted the statement. A new investigation, spurred by mounting public scrutiny and media pressure, revealed the uncomfortable truth: the registrar had erred.

In a May 2025 letter to the Public Complaints Commission, Nnebedum admitted that a review of the 1985 convocation records failed to find Nnaji’s name. Further confirmation came from UNN Vice-Chancellor Simon Ortuanya, who stated, in an official letter dated 3 October 2025, that Nnaji never graduated and was not awarded any degree by the university. According to an internal source, Nnaji failed Virology—a mandatory course—and dropped out. His student file, they say, remains “intact,” clearly documenting his withdrawal before graduation.

So the question becomes: if Nnaji did not graduate, how did he obtain the degree certificate? And if he never graduated, how did he qualify for the NYSC programme, which requires a university degree as a precondition?

There are two plausible answers. First, the degree certificate may have been forged outright—created by underground document forgers who operate in Nigeria’s black market of credential manufacturing. These forgers produce nearly identical facsimiles, but often miss subtle markers like registry serials or watermark patterns.

Second, and more ominously, there may have been internal collusion within UNN’s registry. The initial, now-withdrawn letter from the registrar may suggest that elements within the university bureaucracy either knowingly or negligently aided in the cover-up. That letter has since been disowned, but the question lingers: was it a mistake—or part of a broader pattern of compromised record-keeping?

Whatever the pathway, Nnaji’s actions likely constitute criminal forgery under Nigerian law. According to the Criminal Code, Section 465, forgery is defined as making a false document with intent to deceive. Section 467 prescribes up to three years imprisonment. By submitting false credentials to multiple arms of government—the presidency, Senate, State Security Service, Secretary to the Government—Nnaji may also be liable for false pretence, perjury, and breach of public trust.

Beyond the legal exposure, the political ramifications are seismic. A minister who forged academic credentials to enter office shatters the already fragile credibility of the administration that appointed him. The Tinubu government is now faced with a stark dilemma: remove Nnaji and signal a commitment to integrity—or protect him, and reinforce a narrative of elite impunity.

Nnaji’s case is particularly galling given his portfolio. As Minister of Innovation, Science and Technology, he was charged with overseeing Nigeria’s scientific research institutions, developing innovation policy, and elevating the nation’s technological footprint. His tenure now appears not merely ironic but insulting. A man who forged science credentials was entrusted with leading scientific progress.

The scandal has already sparked a wave of institutional soul-searching. UNN, to its credit, has gone on the record to disown Nnaji’s degree. But questions remain about how such a significant error—if that’s what it was—occurred in the registrar’s office. Universities across Nigeria may now be compelled to audit their own record-keeping systems. The larger question looms: how many other public officials are in office on the strength of forged documents?

And then there is the role of the vetting institutions—the Senate, the SSS, the office of the SGF. How did they all miss this? Was there pressure to approve the nominee regardless of credentials? Were the checks merely superficial? The scandal suggests that Nigeria urgently needs a centralised, independent credential verification agency. Without such reform, fake degrees will continue to slip through the cracks.

What comes next is uncertain. Legal experts suggest that Nnaji could face both civil and criminal action. At minimum, he should be removed from office. At most, he could face trial. The Federal High Court will reconvene on 6 October to hear more arguments in the suit he brought against UNN, the National Universities Commission, and the Minister of Education. The court may compel UNN to release full academic transcripts—a step that could irrevocably cement his disqualification.

Meanwhile, the Tinubu administration remains silent. There has been no official response from the presidency, the Federal Ministry of Justice, or the Senate. But civil society is unlikely to stay quiet. Already, public interest groups are calling for Nnaji’s resignation or removal, and for a sweeping audit of all ministerial appointees.

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of this saga is how routine it has become. Nigeria is no stranger to certificate scandals. Governors, lawmakers, ministers—dozens have faced similar allegations in recent years. Most survive. Some even thrive. The consequence of forgery is too often a slap on the wrist or a quiet reassignment.

But this time, something feels different. The admission is on paper. The university has spoken. The documents have been exposed. And the public is watching. If nothing happens, it will not be because the facts are unclear—it will be because accountability was sacrificed, once again, on the altar of political convenience.

What’s at stake is not just one man’s career—it is the principle that public office should be earned, not falsified. That those who claim to lead must first tell the truth. That in a nation of brilliant, hardworking graduates, there is no place for ministers of lies.