What goes largely unappreciated is that the Delta State government already owns and runs one of the most successful contributory health insurance operations in the Nigeria. It’s taken on the care of millions of Nigeria’s most challenging patients, including residents of hard-to-reach rural communities in Delta State.

Currently, Delta State leads the nation with over a million enrollments; it the only State with the highest enrollment in universal health coverage even more than many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Delta State Government keeps costs generally below average and charges a subsidized Premium for those with capacity to pay Premium and Free for those unable to pay Premium. It earns quality-of-care ratings that most States in Nigeria envy.

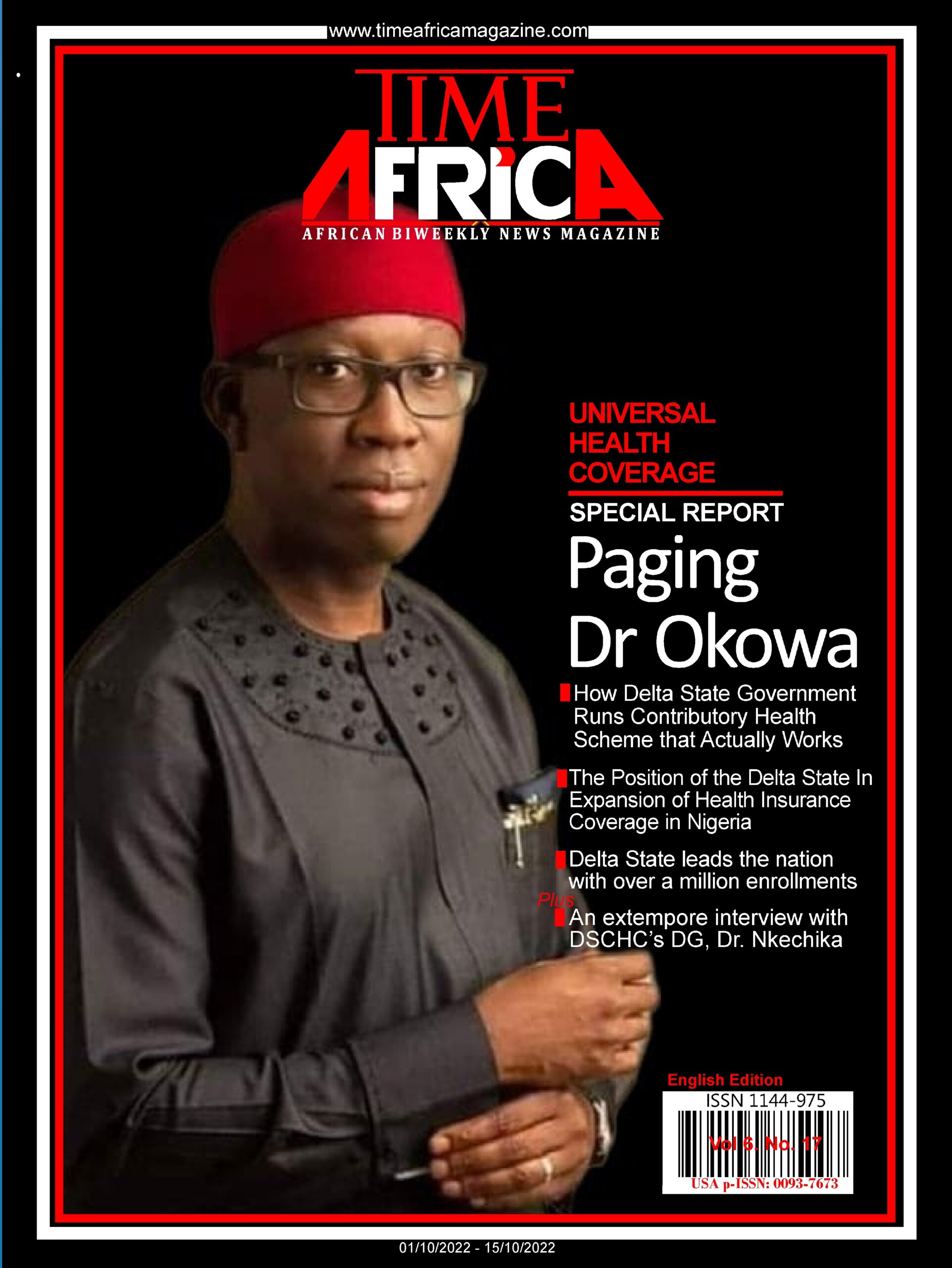

The “Strong and Significant Political Will” of His Excellency Senator Dr Ifeanyi Okowa, Governor of Delta State is the “Game Changer” that has made the difference in Delta State. While he was the Chairman of the 7th Senate Committee on Health, Senator Dr Ifeanyi Okowa championed the passage of the National Health Act (NHA 2014). However, the implementation of the NHA has been suboptimal especially for the BHCPF program across the country. Thus, as Governor of Delta State with Executive Powers, the implementation of the NHA through the Delta State Contributory Health Scheme has been a success story that has received both local and international accolades. The expectation is a success story at the Federal Level with Federal Executive Power.

In his extempore presentation in Abuja – Nigeria during an all-important stakeholders’ conference titled: Expansion of Health Insurance Coverage in Nigeria: The Position of the Delta State Contributory Health Commission, DR. BEN NKECHIKA, the Director General/CEO of the DSCHC, gave am in-depth expository of the global principles of Universal Health Coverage; the successful implementation of healthcare policy of the Delta State Governor, His Excellency Ifeanyi Authur Okowa. He assured of a significant healthcare insurance coverage for Deltans in nearest future to attain the Universal Health Coverage benchmark, while promising to “continue to improve on what is working today and fix what isn’t, so that every Deltan has access to affordable coverage and high-quality healthcare.” Excerpt:

Nigeria established its National Health Insurance Scheme in 1999, with a mandate to attain UHC

Providing access to equitable, affordable and quality health care for citizens has been a significant challenge for many countries. This challenge becomes serious in the face of daunting fiscal challenges, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, governments are engaging in reforms to improve their health systems, mainly on financing health care sustainably for citizens. This concern has also led to mainstreaming the concept of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) into the global health agenda as prescribed in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. Nigeria established its National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 1999, with a mandate to attain UHC. However, since then, coverage has been marginal at less than the current 5 per cent.

Delta State, in 2017, started implementing a state social health insurance scheme based on the Delta State Contributory Health Commission (DSCHC) Law, signed in 2016, to expand health insurance population coverage. The Delta State initiative has provided health insurance service coverage for over 1 million enrollees (about 20 per cent of the state’s population). The successes recorded by the DSCHC demonstrate the critical role of strong political support from the government and elaborate stakeholder engagement for the successful roll-out of any social health protection programme. This approach is corroborated by lessons learned from other countries on the path to UHC, such as Rwanda, Mexico, Thailand and the Philippines.

The Delta State initiative provides proof of concept on the importance of expanding health insurance coverage for the well-being of citizens. The lessons also support the position that integrated, non-fragmented pooling of financial risks for all, especially the vulnerable population, is the most efficient approach to making significant progress towards achieving UHC in Nigeria by 2030. This is in addition to applying sustainable mechanisms to raise adequate resources for financial sustainability and the need for government-earmarked funding and other innovative approaches.

The experiences from the Delta State Contributory Health Scheme (DSCHS) Equity Health Plan for the poor and vulnerable, has shown that the approach significantly impacts population health, as well as micro and macroeconomic indicators, with multiplier effects on population well-being.

It is therefore recommended that the DSCHC model for health insurance coverage be adopted and expanded across Nigeria with a significant focus on poor and vulnerable populations.

The financial constraints make it impossible for government alone to provide UHC sustainable

The financial investment required to expand population coverage in Nigeria is enormous. However, targeting different demographic groups e.g., pregnant women, children under 5 years and the elderly will reduce costs.

Despite these alternatives, the financial constraints currently faced by the Government of Nigeria make it impossible for government alone to provide UHC sustainably. Therefore, there is recommended need for a sustainable pluralistic domestic resource mobilization mechanism for implementation, with the necessary legislative backing, among others. These strategies include the use of insurance-based mandatory contributions, earmarked taxes, donor funding, and other innovative options for mobilization of funds to capacitate and sustain such an initiative.

The DSCHC has explored similar options with significant success. Strong political will, a stable governance system and the utilization of a significant portion of the mobilized funds for the poor and vulnerable population will accelerate progress towards expansion of health insurance coverage and Nigeria’s attainment of UHC by 2030.

The adoption of the SDGs provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity

The adoption of the UHC concept has provided the needed tool, and many countries have committed themselves to this goal through laws, policy documents and declarations, amongst which are the United Nations SDGs.

The adoption of the SDGs by all United Nations Member States in 2015 provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet. It is a call for action by all countries to end poverty and other deprivations, with strategies to improve health and education, reduce inequality and spur economic growth. SDG recognizes the nexus between good population health and sustainable development and reflects the complexity and interconnectedness of the two. It looks at widening economic and social inequalities and the continuing burden of HIV and infectious diseases; aims at achieving UHC, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

Universal health coverage is now the central focus of global health policy, and countries are designing and implementing various strategies and programmes towards its attainment. Achieving UHC requires a well-functioning health system that enables all people to access necessary health services without suffering financial hardship. It is a catalyst for change, leading to a more efficient and accountable health system and an integrated, efficient approach to improve health outcomes. As countries move towards UHC, they need to be guided by its principles: equitable access, efficiency, quality, inclusiveness, availability, adaptability, choice and innovation.

Expanding health insurance to citizens has increasingly become the strategy of choice adopted by many nations, especially low- and middle-income countries. This is because it enhances equity, has prospects for comprehensive coverage, promotes efficiency and is sustainable.

Financial barriers to access health care exist in Nigeria. This is mainly due to inadequate investment, poor funding of health care at all levels, severe inequities in access and lack of coverage by prepayment arrangements. Health-care financing indicators reveal that the country lags in most fields. Health expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic products (GDP) remains at 3.8 per cent, and out-of-pocket expenditure of 76.6 per cent is one of the highest rates globally. Also, coverage with prepayment mechanisms and social safety nets are suboptimal at 5 per cent and less than 2 per cent, respectively. This is further worsened by pervasive poverty and income inequality, making access to quality health-care services through out-of-pocket payments difficult for citizens in Nigeria.

About 83 million Nigerians live below the poverty line

About 83 million Nigerians, or 40.1 per cent of the population, live below the national poverty line with an average income of 137,430 naira (₦) per year (US$381.75). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence shows that as many as 53 million more vulnerable people could further fall into poverty (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Before COVID-19, just 4.4 per cent of the population was covered by at least one form of social benefit or assistance. COVID-19 has further worsened these concerns. Nigeria, India and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are expected to experience the most significant increase in people living under the poverty line due to COVID-19. The attainment of UHC by 2030 is important to combat the increasing challenges of poor health outcomes, with maternal and neonatal mortality in Nigeria being persistently high and accounting for 10 per cent of worldwide maternal deaths (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

Currently, Nigeria has adopted a National Mandatory prepayment mechanism through the recently enacted National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) Act 2022 that repeals the NHIS Act 2004, to tackle its health financing challenges and stem the poor performance of the health system, as revealed by poor health outcomes. This strategy aligns with the broader view that UHC can be effectively attained by introducing mandatory prepayment systems and subsidies for the poor and vulnerable.

Nigerian government established the Basic Health Care Provision Fund as an Earmarked fund for the effective delivery of health-care services

Health insurance was introduced in Nigeria in 1999 with the establishment of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) to drive Nigeria’s UHC agenda. The NHIS designed various programmes targeted at extending coverage to all Nigerians. These included platforms for coverage of formal sector employees, the self-employed, students in tertiary institutions, the armed forces and vulnerable persons such as pregnant women, children under 5 years, the disabled and prison inmates. In addition, the NHIS piloted a rural community-based social health insurance programme aimed at including individuals in rural and low socioeconomic settings. Despite these efforts, estimates show that coverage under the NHIS was less than 5 per cent of the Nigerian population in 2015. In 2015, the federal government, through the National Council on Health, given the challenge faced by Nigeria on its path to UHC and considering the political context and the fact that the Constitution is silent on health, mandated the establishment of state social health insurance schemes by state governments.

To further strengthen the drive to UHC, the Nigerian government established the Basic Health Care Provision Fund as an earmarked fund for the effective delivery of health-care services for all Nigerians. However, since its commencement in 2019, its implementation by the NHIS as a parallel programme with state health insurance programmes has made effective implementation difficult. Some of the noted difficulties include variations in benefit packages, enrolment processes, tariffs, billing/claims management and information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure harmonization. Thus, policy and programmatic divergence persists within the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory.

As a panacea for the increasing challenges, an initiative known as Health Insurance Under One Roof has been introduced as a mechanism for coordination, regulation and integration within the health insurance ecosystem in Nigeria. Despite these efforts, the current coverage level through health insurance remains low and forecasts of Nigeria’s ability to attain the goal of UHC by 2030, judging by current trends, are grim. Therefore, the country needs to redouble and re-evaluate its efforts and strategies to be on track for achieving UHC. Suffice to say that countries making progress on the journey to UHC have implemented context-specific models to finance citizens’ health care, especially of the poor and vulnerable. Funding-integrated health services can positively impact the health and economic development of the population. Adequate resource mobilization, which includes earmarked health insurance funding especially for the poor and vulnerable, is a tactical policy reform for Nigeria’s sustainable human capital development and economic recovery.

Nigeria runs a pluralistic health-care system with public and private sectors and modern and traditional systems providing health care

Nigeria is a lower-middle-income country with a GDP of US$432.29 billion and a GDP per capita of about US$2,097.1. Nigeria operates a federal system of government, with 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory. There are 774 local government areas, each having powers to legislate on health and health-care-related issues. Nigeria runs a pluralistic health-care system with public and private sectors and modern and traditional systems providing health care. Primary health care remains the bedrock and entry into the health-care delivery system.

To a large extent, the country has demonstrated commitments aimed at strengthening its health system and attendant outcomes. It is a signatory to many international obligations, some of which include the Sustainable Development Goals (2015), the Abuja Declaration (2001), the Abuja +12 Declaration (2013) and the World Health Resolution 58:33 on Universal Health Care (2005), to mention a few.

In 2014, the country hosted a summit on universal health coverage, with declarations committing to pursue this global goal. To mainstream these declarations and commitments into national priorities, Nigeria has developed various policies and plans. These are the National Strategic Health Development Plan and its revision, the National Strategic Health Development Plan II; the revision of the National Health Policy in 2016; the development of the National Health Financing Policy in 2017; and the signing into law of the National Health Act in 2014.

The NSHDP II provides the tool and road map for Nigeria to implement these commitments that include, facilitating the expansion of prepayment social health insurance schemes for UHC and addressing the unfinished business of the Millennium Development Goals, the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Post-2015 Development Agenda, including the renewed global commitment for countries to progressively attain UHC. Some of the potential benefits that accrue from the NSHDP II include increasing the share of GDP allocated to primary health care, and using the NHIS to administer 50 per cent of the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund to subsidize state-led social health insurance schemes health insurance premiums for the Poor and Vulnerable, thereby facilitating access for the poor and other vulnerable groups to a basic minimum package of health services. This is in addition to revamping the primary health centres to tackle issues of access and affordability. The NSHDP II projects a target of 30 per cent population coverage by 2022 through risk protection mechanisms and pooled funding increase from the current 5 per cent.

The absence of a mandatory component has hampered NHIS’s ability to expand coverage

NHIS was established under Decree 35 of 1999, now CAP N42 LFN 2004, as a health-care financing mechanism to provide health-care services for all Nigerians and protect them from the financial consequences of huge medical bills, while ensuring optimal service quality. Attaining the specified objectives of the NHIS will help improve the national health outcomes in no small measure.

Unfortunately, since its inception, the scheme has had several challenges that have made it difficult to effectively pursue its mandate. The legal framework that established the scheme did not make it mandatory, unlike in the Philippines, Thailand and Rwanda, where the legal frameworks mandate participation as a critical requirement for UHC attainment. This absence of a mandatory component to Nigeria’s health insurance programme has made coverage beyond federal public sector employees difficult. Thus, the recently enacted NHIA Act 2022 which makes Health insurance Mandatory for all people resident in Nigeria and repeals the NHIS Act 2004, if implemented as specified in the Act, will enhance Nigeria ability to achieve UHC. The DSCHC Law enacted by the Delta State Government in 2016, made health insurance compulsory for all residents of Delta State.

Experience from Thailand and the Philippines shows that formalizing a centralized financing system for the poor and vulnerable contributed to their triumphant progress to UHC, demonstrating the importance of a subsidy contribution for increasing coverage, especially for vulnerable populations. With the poor economic indices in Nigeria characterized by a growing number of persons plunged into poverty, the population of vulnerable persons who will be unable to afford their basic health needs will increase.

Therefore, the country needs to make tough decisions if access and financial protection within the context of health insurance is to lead to expansion of coverage for the majority of its population. Inevitably, there should be several funding strategies targeted at demand- and supply-side interventions to narrow the health funding gaps in the country and improve coverage, particularly for vulnerable people – children under 5 years, pregnant women, etc.

Challenges of the vulnerable paying premiums – the case of DSCHS

Concerns that most Nigerians in the vulnerable groups would be unable to pay premiums could be addressed by adopting the option of installment premium payments and subsidized premium payments for those unable to pay full premium, successfully implemented by the Delta State Contributory Health Scheme (DSCHS).

Experience from the DSCHS shows precisely that individuals in poor rural communities can be asked to pay as little as ₦500 (approximately US$10) weekly over a specific period to raise the annual insurance premium. This innovative financing for premium payment could be supported through subsidy by all tiers of government and donors to enable rural community residents to rapidly meet their premium payment obligations.

The Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana in India is an innovative demand-side model where federal and state governments subsidize individual payments of premiums for health insurance. The same policy applies in the cases of Rwanda and Ghana. Supply-side strategies will also include increased budgetary allocations to meet the Abuja Declaration of a minimum of 15 per cent of national budgetary allocation to health, with more coherent and reprogrammed public financing mechanisms.

The success stories of DSCHS and it aims to achieve UHC by the year 2030

The DSCHS is the health-care financing system established by the Delta State government to ensure access to quality health-care services for all residents of Delta State, irrespective of their socioeconomic status and geographical location. The DSCHS aims to achieve UHC by the year 2030.

The journey towards achieving UHC for residents of the state commenced with an executive bill to the Delta State House of Assembly on 22 June 2015, to establish the Delta State Contributory Health Commission (DSCHC). The bill went through legislative processes and was passed into law on 9 December 2015. It was signed into law by His Excellency, Senator Dr. Ifeanyi Okowa, Governor of Delta State, on 4 February 2016, making Delta the first State to commence the implementation of a mandatory health insurance scheme in Nigeria.

The law established the DSCHC, the DSCHS and other matters connected to it, as well as a governing board for the DSCHC, which regulates, supervises, implements and ensures the effective administration of the mandatory DSCHS for all residents of Delta State. The law specifies that the Governing Board should be composed of only representatives of critical stakeholders, based on contributions and other statutory functions.

The management structure of the DSCHC comprises a Director-General/Chief Executive Officer as the Chief Accounting Officer, appointed by the Governor with a renewable tenure of four years, subject to confirmation by the House of Assembly. The management structure also includes six director s for the six departments of the commission and personnel for each department.

DSCHC commenced implementation of valid programmes

The DSCHC, which commenced service delivery under the scheme on 1 January 2017, has enrolled over 1.2 million residents of Delta State (approximately 20 per cent of the estimated total population of the State) in six years of operation, compared to the NHIS enrollee population of less than 5 per cent in 16 years.

The DSCHC Law provides a single pool of DSCHC funds with a unitary risk-bearing structure, devoid of fragmentation during implementation. All contributions from the government and enrollees, as well as other accruable funds, are domiciled in the single Delta State Contributory Health Scheme Fund. Services are purchased directly by the DSCHC through a well-structured strategic purchasing arrangement with public and private health-care providers. The DSCHS implements a single minimum benefits package for all enrollees, irrespective of their socioeconomic status and contribution value. Through a “Strategic Purchasing Program”, the provider payment mechanisms used are capitation for primary care, fees for service for referral secondary care cases and an innovative performance-linked provider payment option referred to as ‘diagnosis-related groups’.

The DSCHC commenced implementing the Access to Finance (A2F) Programme to ensure availability and a good spread of health-care services across the state. The A2F Programme is an innovative, collaborative endeavour where reputable private providers are supported to access financing and contracted under a public-private partnership arrangement to provide quality health-care services in hard-to-reach rural areas, abandoned public health-care facilities in rural communities or communities bereft of a functioning health-care facility. The A2F Programme has been recognized as the most strategic and vibrant, innovative public-private partnership programme for revitalizing defunct primary health-care service delivery in Nigeria.

Over 70 per cent of the DSCHC total enrolment consists of poor and vulnerable people

To enhance the poor informal sector enrolment status, the DSCHC commenced implementing the Indigent Support Programme to mobilize funding for the enrolment of the poor informal sector and most vulnerable population into the scheme. Prominent Deltans, corporate organizations and other philanthropists are encouraged to contribute annually to the DSCHS pooled funds to pay for indigent Deltans or complete payment for those who can make initial premium payment commitments.

The DSCHC has an installment premium payment as a payment option in poor rural communities. The Identifiable Group Taxation Programme is a flagship initiative specially designed for artisan groups. Artisan groups make up a significant proportion of the informal sector population. They are identified and a fraction of their daily or weekly payment, previously remitted for tax payment, is transferred to the DSCHC as payment for their health insurance premium. These payments are recognized as statutory tax payments with the issuance of a tax payment certificate.

The DSCHC operates with a robust and integrated ICT system that is compliant with the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC), National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), as well as Nigeria Data Protection Regulations (NDPR). All the supply- and demand-side health insurance business processes are electronically enabled, including a deployed Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Application.

The practical implementation of the DSCHS has also made a substantial financial impact on various aspects of the health system in Delta State. About US$12 million has been injected into the health-care delivery system through provider service payments within Six years of operation. To ensure the availability of quality drugs, especially for critical health-care conditions that require long-term management and are expensive (e.g., hypertension and diabetes), the DSCHC signed a contractual agreement with Servier Pharmaceutical Ltd. and Sanofi Pharmaceutical Ltd. to provide discounted high-quality drugs. These drugs are made available to all enrollees of the scheme at no extra cost. The contractual agreement also includes capacity enhancement of health-care providers on better management of diabetes and hypertension and establishing specialized diabetes and hypertension clinics within selected health-care facilities in the state’s three senatorial districts.

Suffice to say that the gains from the inclusion and implementation of the mandatory enrolment clause in the DSCHC Law are evident, considering the level of coverage achieved by the DSCHC over a short period of Six years. Although more needs to be done, especially for the informal sector groups, the lessons from Thailand, the Philippines and Rwanda corroborate the above evidence.

The scheme’s sustainability is strengthened by the mandatory requirement in the DSCHC Law, which provides for public funding from the State Consolidated Revenue Fund. Payment of health insurance premiums for the poor and vulnerable population are all covered under this provision. Over 70 per cent of the DSCHC total enrolment consists of poor and vulnerable people, the highest in the country. Given this lofty achievement, the DSCHC was recognized as having the most outstanding state government health-care programme and awarded a certificate of excellence for having the best health insurance coverage in Nigeria focusing on the poor and vulnerable population, under the World Bank/Federal Government Save One Million Lives Programme in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

Governor Okowa’s effect

Successes recorded by the DSCHC and DSCHS have been due mainly to strong political will, demonstrated by His Excellency, the Governor of Delta State, Senator Dr. Ifeanyi Okowa. This is in addition to the diligence of the success drivers of the scheme, including a well-articulated governance structure to implement the mandatory health scheme; elaborate stakeholder engagement across the various strata of the society; the robust, integrated ICT system; the innovative pooling of resources; and strategic purchasing activities deployed to ensure an equitable spread of quality health-care service delivery across the state.

Quick expansion of health insurance in Nigeria will boost the economy, finance and social lives

Accelerating the expansion of health insurance in Nigeria and addressing health inequalities will foster economic, financial and social benefits for the country and the vast majority of its citizens, especially those that are vulnerable. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, 40.1 per cent (i.e., 83 million people) of the total population in Nigeria live in poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn attention to the need for expanding health insurance and specifically to the fact that out-of-pocket health expenditure is 76.6 per cent, with less than 5 per cent health insurance coverage in the formal sector and only 3 per cent of people covered by voluntary private health insurance in the informal sector. One cannot overemphasize the need to strengthen the resilience capacity of Nigeria’s health insurance system, ensuring it provides counter-cyclical support in times of challenge for the most vulnerable population who may be forced to adopt negative coping behaviors to survive.

Economy: In Nigeria, expanding health insurance should be a strategic policy reform for sustainable human capital development and economic recovery. Evidence exists of the benefits of population health and health investments on economic growth. For instance, it has been demonstrated that expanding health insurance coverage would impact the nation’s economy by increasing the GDP per capita spent on health- care delivery and human capital development and productivity. Expansion of health insurance for the vulnerable population is associated with reduced out-of-pocket medical spending, increased financial stability, improved material well-being for families and many short- to long-term poverty-reducing effects. There is also evidence that the introduction of health insurance may improve health expenditure in Nigeria, with prospects for gradual realization of the Abuja Declaration.

There is also significant evidence that expanding health insurance coverage improves microeconomic indicators such as household economy and impacts on population productivity with multiplier effects.

Financial benefits and poverty-reducing effects: The primary economic purpose of health insurance is to protect those covered from financial risk. These risks include, but are not limited to, becoming ill or injured and needing expensive medical care. Health insurance, particularly with little or no cost-sharing such as in the Delta State health insurance schemes, may also help with the affordability of non-catastrophic medical care, such as routine preventive and chronic disease management. There are, therefore, contentions that the provision of health insurance for vulnerable socioeconomic groups could play an important role in a comprehensive system of protection against risk, including other ex-ante measures such as promoting credit and savings and a credible overall social safety net. For instance, the economic cost of treating malaria in Nigeria ranges from US$9.14 to US$37.99 per episode of uncomplicated malaria, at a median cost of US$22.48. At the subnational level, the annual premium paid by an enrollee in the DSCHS informal sector is ₦7,000 (US$17.03), which covers a wide range of health-care services as listed in the DSCHS health benefits package. An enrollee covered under the DSCHS at a cost of US$17.03 for the DSCHC full health benefit package, which includes treatment of both uncomplicated and complicated malaria for one full year, would not have to bear the out-of-pocket, once-off cost of US$22.48 for malaria treatment.

Health insurance promotes credit and savings for populations through its inherent financial protection feature, by freeing up resources for the household that can be re-allocated for other needs. Lessons from Mexico, Columbia, China, India, Thailand and Rwanda consistently point to this capacity to reduce spending on catastrophes by individuals and families and provide proof of concept of the financial benefits of expanding health insurance coverage for Nigeria.

Social benefits: The social benefits of expanding access to quality health-care services include enabling individuals (especially children) from low-income families to achieve their social and mental development and educational milestones, and increased human productivity through good health care and linkage to other social protection and safety nets. Children in all population groups are noted to be the most vulnerable and benefit the most when included in a social protection mechanism.

Essentially, the inclusion of children in a health insurance scheme provides financial risk protection at the point of health services delivery, with increased utilization and improved health outcomes. This position has been demonstrated in Nigeria’s Jigawa, Bayelsa, Cross- River and Ekiti States through their sponsored demand-side interventions for mothers, newborns, children and other vulnerable populations. Similarities exist in Thailand’s Universal Coverage Scheme, the Children’s Health Insurance Program in the United States of America and the Equity Health Plan of the DSCHS in Delta State Nigeria, where free antenatal care coverage is provided for pregnant mothers to ensure a healthy mother and foetus; free delivery for continuity of health of mother and child; and free under-five years health-care services to ensure proper early childhood development with a future significant multiplier effect.

There is also evidence of improved educational attainment for eligible cohorts, with higher reading test scores later in childhood and increased high school and college completion rates. In summary, access to health insurance for children and other vulnerable groups has been demonstrated to have long-term positive effects for both health and economic outcomes.

Recommendations for expanding health insurance in Nigeria

Nigeria should adopt a well-designed purpose-driven framework and a non-fragmented and strategic implementation process for Health Insurance service delivery. This should include a capacitated dynamic management system with a clear definition of roles for all stakeholders in the health insurance landscape.

Specific elements of the expanded health insurance programme to attain UHC in Nigeria by 2030 should include:

- Strong and significant political will from the leadership;

- A mandatory health insurance scheme backed by law;

- Public finance subsidies for the poor and vulnerable, backed by law, to ensure equity in access and to leave no one behind;

- Implementation of earmarked innovative health-care financing mechanisms, e.g., the introduction of telecoms tax, sin tax, etc.

- An integrated pooling system involving a single pool at state and federal level with an equalization mechanism;

- Implementation of an elaborate, robust and integrated health insurance ICT system across the country;

- Technically competent and trained human resources for quality health-care service delivery at all levels;

- Wide ranging and regular stakeholder engagement to ensure ownership and support for the programme;

- An integrated health insurance strategic purchasing ecosystem that includes integration of benefits packages, tariffs, ICT, data, monitoring and evaluation; and

- Success drivers who take on the personal responsibility to ensure the successful implementation of a well-designed health insurance programme.