When religious trust meets legal power, the consequences can reshape institutions. That is the unsettling reality now facing Tansian University—a Catholic-founded academic institution in Nigeria—after leaked documents revealed that its legal affairs may have been commandeered under ethically questionable terms by the self-assumed Chancellor of the University, Rev. Fr. Dr. Edwin Obiora.

The document, obtained exclusively by this reporter, outlines sweeping financial entitlements and binding obligations that some experts say amount to a “legal vice grip” on the university.

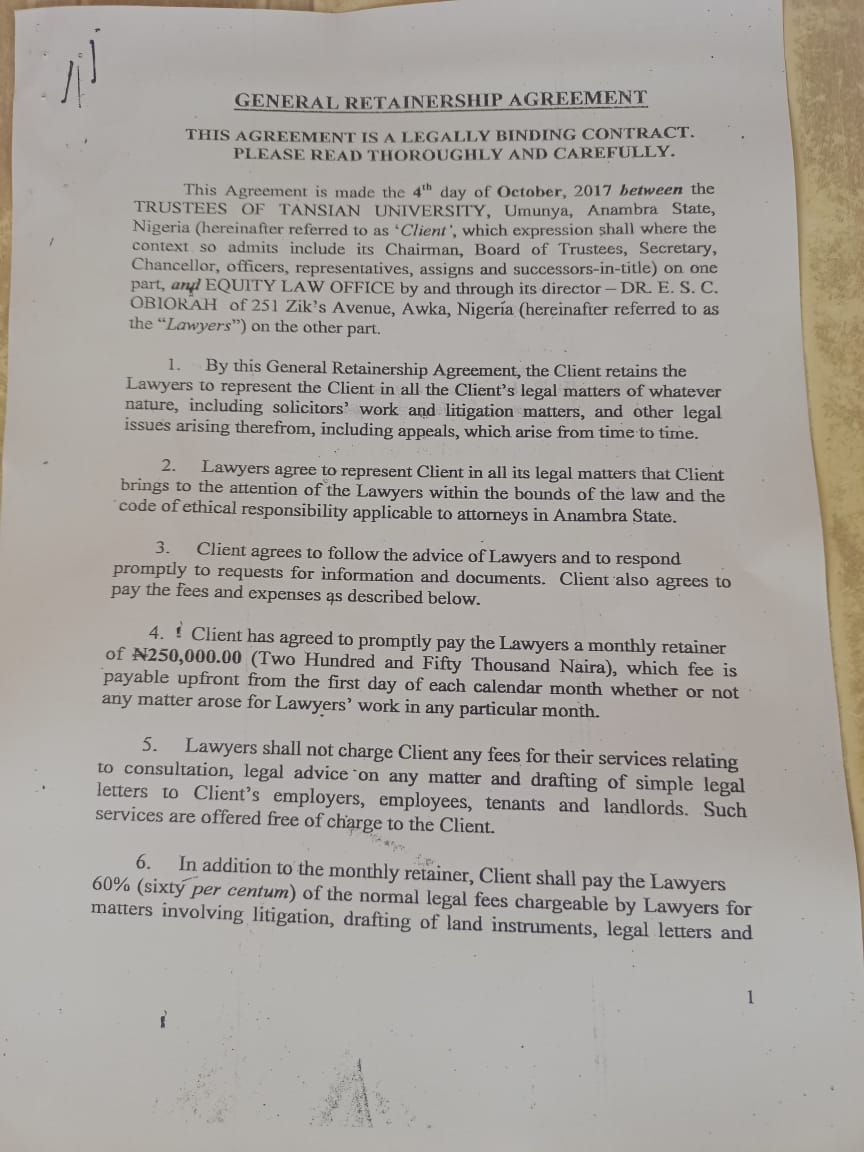

A 22-clause legal agreement signed in 2017—long buried in institutional files and shrouded in ecclesiastical silence—has emerged not for its complexity, but for the brazenness of its construction and the moral incongruity of its architect. The legal instruments was not just protect the institution, but to control it.

But what makes this story far more than a legal anomaly is the spiritual dimension. Fr. Obiora did not come to Tansian University merely as legal counsel; he arrived wearing the Roman collar, under the trust and fraternal relationship with the institution’s late founder, Very Rev. Msgr. Prof. John Bosco Akam. According to insiders, Akam, a respected cleric and academic, had extended that trust to Fr. Obiora as both a fellow priest and professional. That trust, these same sources now claim, was ultimately manipulated through a contract that prioritized fees over fairness, and control over collaboration.

The General Retainership Agreement, signed on October 4, 2017, between Tansian University and Obiora’s law firm—Equity Law Office—grants extraordinary powers to the priest-lawyer, including a 60% legal fee on undefined sums, monthly retainers regardless of services rendered, and the right to demand security, including mortgaging institutional assets. There are few limits placed on the scope of representation or the financial obligations it imposes.

Legal analysts who have reviewed the document describe it as “exploitative,” “borderline predatory,” and “unfit for any academic institution.” But for a Catholic university, whose founding principles are rooted in service, ethics, and the moral guidance of its clerical leaders, the implications run even deeper. This is not just a case of contract abuse; it is a crisis of moral leadership—one that raises urgent questions about accountability, fiduciary responsibility, and the power dynamics at the intersection of faith and law.

At the center of the document lies a 60% legal fee attached to an unspecified base, tagged as neither an estimate, nor a minimum, nor a maximum. Instead, it is an elastic figure — with no cap, no floor, and no accountability. Even more disturbing is the clause allowing the lawyer to demand a mortgage on the client’s home (or other security) if this 60% “initial fee” is exhausted before a matter is resolved — a clause that legal experts are calling ethically dubious and borderline predatory. Yet, the client in this scenario wasn’t just any commercial entity. It was Tansian University.

Fr. Obiora is not just a lawyer; he is a priest — a man expected to embody humility, sacrifice, and service. But within this agreement, signed under the auspices of legal representation, many now see the markings of greed, manipulation, and exploitation. According to sources within the university, “we trusted him because he wore the cloth,” said one board member who asked not to be named. “But what he wore underneath was a contract meant to fleece the university dry.” Clause by clause, the agreement constructs a legal vice grip that prioritizes billing over resolution, penalties over partnership, and power over equity.

Let’s break down just a few of the troubling provisions in the document: Uncapped Fees – the 60% fee attached to an undefined base creates a shifting burden, where the financial obligations could soar without the client’s awareness or ability to manage expenses. This indecipherable structure placed Tansian University in a vulnerable position, exposed to overreach and exploitation.

The intricate details of the agreement reveal a web of clauses that, while presented as standard legal language, contains manipulative elements that placed the university in a precarious position. Tansian University, acting through its representatives, engaged Dr. Obiorah under the belief that they were enlisting professional legal counsel. However, the agreement’s broadly defined scope—allowing representation in “all legal matters of whatever nature”—grants Dr. Obiorah an expansive authority that have led to unwarranted legal actions and excessive financial liabilities. This open-ended engagement has left the university vulnerable to a barrage of legal services that are not needed, just to create an environment ripe for debt accumulation.

The retainer fee set at N250,000.00 (Two Hundred and Fifty Thousand Naira) each month, required upfront regardless of the services rendered, raises significant concerns about the financial implications for Tansian University. Regardless of whether any legal matters arise, the university is locked into paying this considerable fee—an obligation that strains financial resources, especially for an educational institution already navigating economic challenges. In addition to this retainer, the agreement stipulates that Tansian University must pay 60% of normal legal fees for any services related to litigation and other legal responsibilities. Such a dual obligation have spiraled into a heavy financial burden, especially as Fr. Obiorah pursues a multitude of legal avenues that entailed substantial costs.

While the agreement outlines certain legal services as free, the vagueness surrounding what constitutes “simple legal letters” and “consultations” lends itself to ambiguous interpretations. Fr. Obiorah’s manipulations of these terms have led to unexpected expenses for the university. By labeling extensive consultations as “simple,” he sidestepped the agreement’s promise of free services, leaving the university with unforeseen bills. The clause mandating that Tansian University must follow the advice of the lawyers creates an imbalance in the client-lawyer relationship. Fr. Obiorah’s authority as a legal representative pressured the university to accept directions that do not align with their interests. This compliance requirement decreased the university’s autonomy, ushering in decisions that reinforce Fr. Obiorah’s control while jeopardizing the institution’s financial health.

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of this agreement was the apparent lack of provisions that allowed Tansian University to terminate the contract without severe implications. The inability to exit disadvantageous relationship only compounds the risk of accumulating even more debt, as the university may find itself compelled to continue seeking legal counsel from Dr. Obiorah, regardless of performance or suitability.