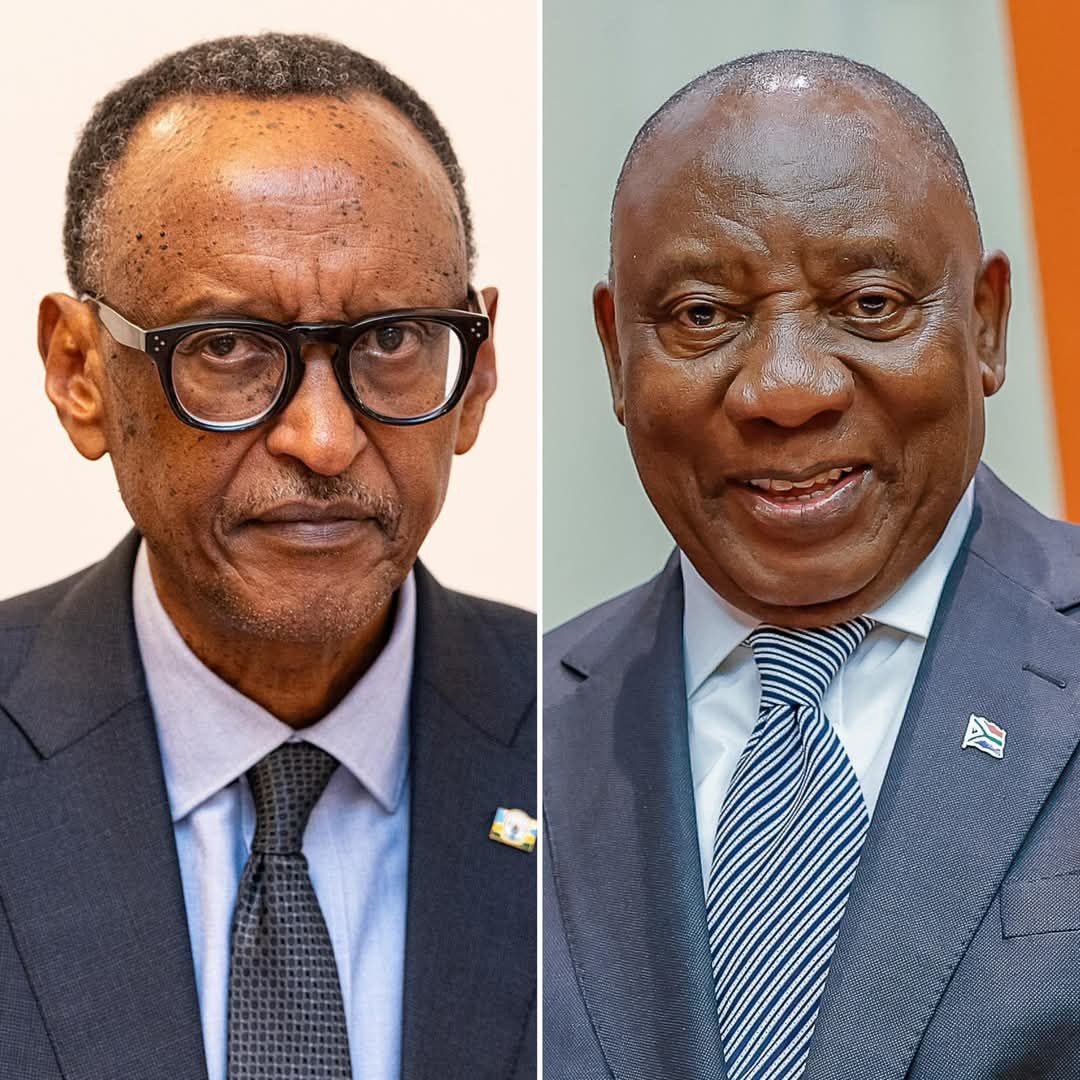

Tensions between South Africa and Rwanda have erupted into a diplomatic showdown, with both countries exchanging sharp words amid the ongoing conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). While their forces are fighting on opposing sides, South Africa’s involvement in the region has sparked an escalating war of words. With the recent deaths of South African soldiers in clashes with M23 rebels, allegedly backed by Rwanda, South Africa is now facing not only internal backlash but also fiery threats from Rwandan President Paul Kagame, who has lashed out at President Cyril Ramaphosa’s comments.

Apparently, the war in the eastern DRC is also stirring up old disputes between the two countries.

The mission in the eastern DRC is turning into a serious quagmire for South Africa’s government. First, it must reckon with heavy losses: 13 soldiers were killed in the battle for Goma on 23 January, launched by M23 rebels and their Rwandan backers. South Africa supplies the largest contingent to the SAMIDRC, a regional military force dispatched by the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Next, President Ramaphosa faces criticism at home, where the public questions sending troops to fight in a far-off country. Thirdly, South Africa must deal with threats from Rwanda’s president, Paul Kagame. He rejects blame for the conflict and regards the South African intervention as hostile.

“South Africa’s military presence in the eastern DRC is not a declaration of war against any country or state,” Cyril Ramaphosa insisted in a statement Wednesday. Yet, in that same note, he accused the M23 rebels and the Rwandan army — dismissed as a “militia” — of attacking the peacekeepers sent by SAMIDRC.

“When we were at Goma, the DRC forces were fighting Rwandan forces over our heads. That is where we lost three people. So we had to quickly communicate with M23 to say ‘we are not part of the battle so don’t fight over our heads’,” Angie Motshekga, the South African defence minister said at a press briefing on Wednesday. “President Cyril Ramaphosa did warn them to say if you are going to fire at us we will take it as a declaration of war and we’ll have to defend our people and that’s when the firing also stopped.”

Those comments and Ramaphosa’s statement enraged Kagame. On X, he called them “misrepresentations”, “deliberate attacks” and even “lies” at odds with his phone discussions with Ramaphosa earlier in the week.

The talks were “productive, with no threats or accusations,” says Olivier Nduhungirehe, Rwanda’s foreign minister. According to him, Ramaphosa even suggested the soldiers who died were killed by the Congolese, with whom they are supposed to be working.

Asked to confirm this account, the South African presidency had yet to respond at the time of writing this story.

In another statement, South Africa’s army blamed the deaths of three soldiers on Monday on mortar fire from M23 that landed in their base.

The war of words warrants attention because Rwanda does not view SAMIDRC as a peacekeeping mission.

“It was authorised by SADC as a belligerent force engaging in offensive combat operations to help the DRC government fight against its own people, working alongside genocidal armed groups like FDLR which target Rwanda, while also threatening to take the war to Rwanda itself,” Kagame wrote on X.

“Cyril Ramaphosa is behaving as if he were some peacemaker,” he quipped, while addressing the East African Community (EAC) via videoconference on Wednesday.

Several military experts, although less scathing, agree that SAMIDRC is not really a peacekeeping force in the strict sense. Its mandate is to help Kinshasa “neutralise negative forces and armed groups in eastern DRC in order to restore and maintain peace and security.”

However, in a speech to the nation on Wednesday, President Félix Tshisekedi praised the SAMIDRC soldiers “who are fighting alongside us”.

“Peacekeeping usually refers to lightly armed forces whose job is to stand between warring parties, monitor ceasefires and prevent further clashes,” explains Darren Olivier of the African Defence Review. The next level up is peace enforcement, which allows direct combat to neutralise conflict parties.

“SAMIDRC’s mandate explicitly authorises it to help the FARDC [the Congolese army] and to engage in direct fighting to pursue and neutralise non-state armed groups,” the military expert says. Even so, he points out that “until now, most of SAMIDRC’s activity has been defensive—protecting their bases and trying to secure the road linking Sake to Goma.”

This semantic wrangling reflects the confusion over SAMIDRC’s remit, and the complexities of a local war with regional ramifications.

The conflict in eastern DRC also rekindles old animosities between South Africa and Rwanda. Pretoria suspects Kigali of carrying out extrajudicial killings on South African soil, targeting Rwandan dissidents. In 2014, Patrick Karegeya, a former Rwandan intelligence chief in exile in South Africa, was found strangled in his hotel room.

For now, diplomatic channels remain open, according to South Africa’s foreign minister.

The spat has not escalated, says Nduhungirehe, adding he did not ring his South African counterpart, Ronald Lamola, to scold him. Yet he was displeased with the South African defence minister’s “hostile statement”, which supposedly urged the UN Security Council to condemn Rwanda outright.

Nduhungirehe regrets “unacceptable attacks by South African ministers”, particularly as he believes the two presidents’ phone calls signalled “a good start”.