There was a time when the better off flaunted their status by buying mansions, driving fancy cars, and wearing top hats. Today privilege is commonly assumed to be shameful. Western elites now prefer to sport superior moral status by championing fashionable “progressive” causes. These are “luxury beliefs” because they cost the elites nothing, while costing others a lot. One such cause is that of “decolonisation”, which defames Britain’s four-hundred years of colonial endeavour as a simple litany of racism, exploitation, and oppression – of which slavery is the epitome.

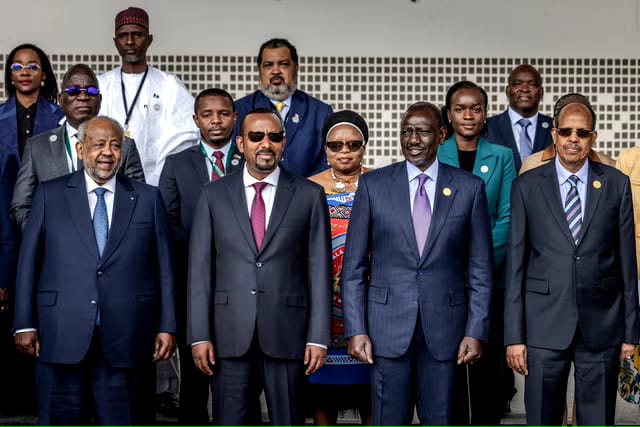

Now, however, “decolonisation” threatens to become very expensive indeed. For, exploiting the West’s performative orgy of self-flagellation, the African Union has just joined the Caribbean Community (“Caricom”) in demanding reparations from Britain for its “colonial crimes”. Caricom has already submitted its bill of £18 trillion. The African continent’s claim is bound to be even higher.

But the cartoonish “decolonising” tale of rapacious British colonisers exploiting helpless African victims is a caricature of the historical truth. Take the issue of slavery. Africans had been enslaving other Africans for centuries. Those they didn’t consume in human sacrifices they sold first to the Romans and then to the Arabs. A few years before the first British slave-ship arrived on the West African coast in 1563, a Portuguese witness had reported that the African kingdom of Kongo was exporting between four and eight thousand slaves annually.

Three hundred years later, Omani Arabs were running slave-plantations on the coast of East Africa, and Fulani Africans were running them in the Sokoto Caliphate in what is now northern Nigeria. Indeed, according to the historian Mohammed Bashir Salau, the Caliphate became “one of the largest slave societies in modern history”, equaling the United States in the number of its enslaved (four million).

Meanwhile, the British had repented of their involvement in slave-trading and slavery, and in the early 1800s were among the first peoples in the world’s history to abolish them. They then used their global dominance, following the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, to suppress both the trade and the institution from the Pacific North-West, across Africa and India, to New Zealand. In mid-century, the Royal Navy devoted over 13 per cent of its total manpower to stopping slave-traffic between West Africa and Brazil.

At the same time, Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton’s idea that the key to ending the slave trade and slavery in Africa was to promote alternative “legitimate” commerce was gaining traction. This led to the setting up of trading posts in West Africa, and then, when the merchants complained of the lack of security, a more assertive colonial presence on land.

In 1851, having tried in vain to persuade its ruler to terminate the commerce in slaves, the British attacked Lagos and destroyed its slaving facilities. Ten years later, when an attempt was made to revive the trade in 1861, they annexed Lagos as a colony. Observe the developmental logic of “colonialism” here: first, the humanitarian intent; then the promotion of commerce; and finally, the imposition of colonial rule.

Contrary to the claim of Caricom reparations champion, Sir Hilary Beckles, African rulers generally opposed British anti-slavery efforts. The Beninese historian, Abiola Félix Iroko, has written that “[w]hen the slave trade was abolished [by the British], Africans were against abolition”. John Iliffe, Professor of African History at Cambridge University, agrees, writing that “[m]any African leaders resisted the abolition of the slave-trade. Kings of Asante, Dahomey, and Lunda all warned that unsold captives and criminals would have to be executed”.

Unlike the cheap performance of “decolonising” virtue, the sustained British campaign against slavery was expensive in both lives and money. Seventeen hundred sailors died in the service of the Royal Navy’s campaign to stop maritime slave-trading. Meanwhile, on land, Christian missionaries risked – and often spent – their lives striving to shut down slave-markets in Africa. Among them was the Anglican bishop, Charles Mackenzie, who died horribly of blackwater fever in what is now Mozambique in 1862 at the age of 37.

David Eltis, described by Henry Louis Gates of Harvard University as “the world’s leading scholar of the slave trade”, reckons that nineteenth-century expenditure on slavery-suppression outstripped the eighteenth-century benefits. And the political scientists, Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape, have concluded that Britain’s effort to suppress the Atlantic slave trade alone in 1807–67 was “the most expensive example [of costly international moral action] recorded in modern history”.

The African Union’s demand for colonial reparations is an act of cynical opportunism. But unless our elites learn to care less about signalling their virtue and more about doing justice to their own country’s historical record, it will cost us all.